Foreign aid, as envisioned and applied throughout the 20th century, has long functioned as an approach to enhance the livelihood of local populations and to provide resources for certain aspects of society that have been unfunded by domestic means. When applied in the best of circumstances, foreign aid exists to be wary of not crowding out local investments. The best implementations of aid are those whose feasibility and prospects are long-studied and modeled in think tanks and offices in the chambered halls of western democracies. Foreign aid has played a significant role in times of emergency relief, and refugee crises, and as a temporary means to improve the quality of life in low-income and lower-middle-income economies.

To be effective, and more importantly, to be sustainable, aid by its very nature has to exist as a short-term and interim solution to any type of problem; be it a natural disaster or fighting corruption that frequently finds itself inextricably intertwined into the fabric of national economies. USAID, one of the world’s foremost providers of aid, states in its name, Agency for International Development that its goal is development and not aid. Accountability and verifiability are the most painful thorns in the side of assistance campaigns or initiatives. In 2013, the European Union suspended financial relief to Uganda after several of its ministers admitted to embezzling over $13 million worth of aid. The ongoing multinational effort to rebuild Afghanistan has faced withering criticism after reports of its government squandered hundreds of billions of dollars in reconstruction funds.

Despite its susceptibility to misuse, foreign aid will always play a role in international development, regardless of what the statistics continue to show. When aid campaigns increase in longevity and their scope widens, the propensity for abuse and corruption seems to grow in tandem. Perhaps arguments can be made that aid is best designed and implemented as a response to humanitarian crises or short-term projects with well-vetted beneficiaries. Although aid helps people and societies, it does not empower them, nor is it intended to. Empowerment comes in the form of providing the tools and means to obtain self-sufficiency. Self-sufficiency only results after years and years of developing skills and refining a craft. Developing skills lead to means of production which leads to the creation of industry.

No nation has ever gone from middle income to high income without industrial means of production and generations of improving processes to trade on the international scale and become connected to the world economy. When economies lack industrial competencies, foreign direct investment can catalyze industrial growth. Using publicly available data from the World Bank and the UN Conference on Trade and Development Policy, we will take a look at how FDI has impacted the nations of Sub-Saharan Africa. The countries in this region belong to the low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income World Bank categories.

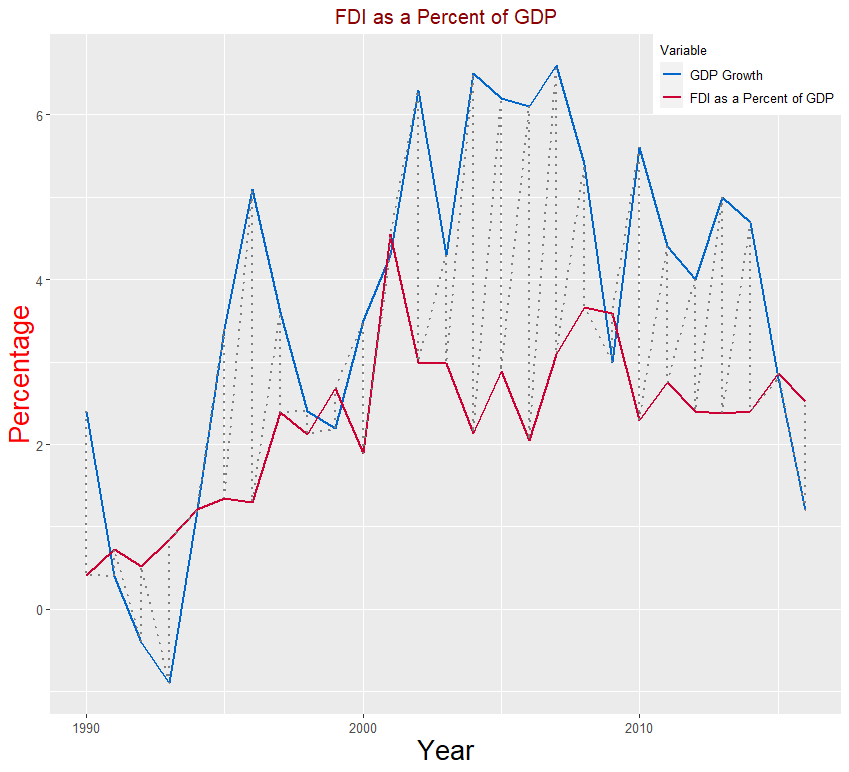

As an aggregate, Sub-Saharan Africa has seen the GDPs of its member countries fluctuate between 1990 and 2016. Across the continent, however, inflows of FDI as a proportion of the economy have made a gradual but steady upward trajectory. Despite this, the region has attracted comparatively low FDI levels compared to the rest of the world. From 2010 to 2016, the continent attracted only 1.8% of global FDI. A seeming paradox exists with FDI in Africa. Parts of the continent are replete with natural resources while supplying a relatively cheap labor force by global standards. Africa also offers a higher return on investment than most of the world at 11% compared to the global average of 7.1%. A few bottlenecks continue to exist, however, such as political instability and concern about human capital.

Figure 1 shows us, however, that some nations are embracing FDI as it continues to contribute a larger portion of their GDPs. FDI has increased in Africa over the past decade with China becoming a major investor in infrastructure projects. At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in 2018, China announced new funding in the form of $60 billion in credit lines, grants, interest-free loans, and investment financing. The new capital allows an easier flow of goods in the form of roads and rails, increased industrial capacities, and with it the rise of a new middle class.

Acts of foreign investment may be applauded for having been conceived in a spirit of altruism, however, this is seemingly the result of a byproduct than the stated goals. FDI decisions are meticulously planned and analyzed for their ROI feasibility. When a foreign labor force can fulfill the same tasks as its domestic counterpart with comparatively minimal initial investment, the upfront FDI expenses often become cost-efficient. Throughout the 20th century, China served in large part as the world’s factory largely due to its cheaper labor force and highly efficient means of production. As it began to industrial heavily in the 1980s, its middle class began to emerge. While China’s industrial transformation has not been described as a revolution, its transition expanded its human capital and raised millions from abject poverty. The new capital gave China the ability to invest overseas and for the past two decades, a significant source of its outsourcing has been taking place in Africa.

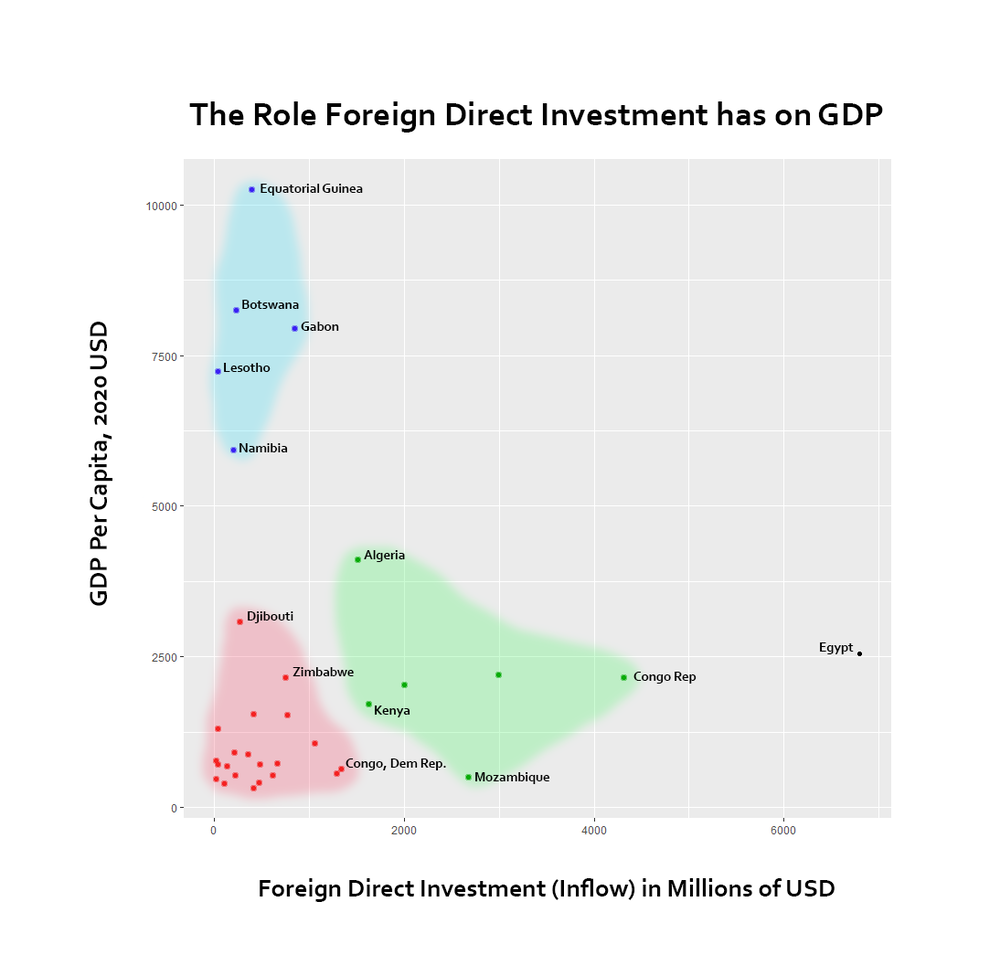

The most visible beneficiaries of FDI are the industries most impacted by investment projects. Figure 2 takes a step beyond the obvious recipients and looks at countries where a micro-level benefit could be correlated with foreign investment. Using 2018 data, three distinct clusters emerge from this aggregate of 33 Sub-Saharan countries, with Egypt appearing as a notable outlier.

The blue cluster represents countries that have received the highest amount of FDI in 2018 as well as those with the highest GDPs per capita. The countries in this group have relatively small populations, with each member having under three million citizens. While not conclusive, these three factors suggest that foreign investment is likely contributing in part to the financial well-being of significant amounts of the populace. When populations are smaller, the long-term effects of investment projects have more impact on residents. In commodity-based economies, large sectors of the population are likely to be involved in industrial fields and more impacted by FDI.

The member countries comprising the green cluster outperform the red in terms of FDI inflows, but not necessarily on the scale of GDP per capita. While the population plays a considerable role in the way FDI trickles down to every segment of the population, there are many other factors at play. A red sub-cluster of countries appears near the intersection of the X and Y axes. The countries in this group have economies less attractive to foreign investors. This could be due to several factors such as autocratic governments, lack of natural resources, or lack of an ROI for any investment.

As governments in Africa grapple with corruption, inflation, and civil war, the ones endowed with natural resources and functional governments will begin to widen the economic divide. The countries clustered near the bottommost corner of this graph will likely continue to receive aid from foreign entities, however, reforms or revolutions will likely need to occur before they become attractive to overseas investors. Any meaningful change will need to come from within domestic borders. Once this happens, their FDI profiles will rise considerably. While FDI will not come close to remedying all ills, it has the potential, as we have seen to catalyze means of production and usher in economic expansion.

Figure 1 shows us, however, that some nations are embracing FDI as it continues to contribute a larger portion of their GDPs. FDI has increased in Africa over the past decade with China becoming a major investor in infrastructure projects. At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in 2018, China announced new funding in the form of $60 billion in credit lines, grants, interest-free loans, and investment financing. The new capital allows an easier flow of goods in the form of roads and rails, increased industrial capacities, and with it the rise of a new middle class.

Comments